BY STEVEN HIGH

Illustration 4: Mayor Camillien Houde & Lord Bessborough (flanked by two sleeping car porters). 1930. McCord Museum.

It is not every day that you get the opportunity to get to know the man behind the voice. But this is precisely what happened to me over two sunny days in February as I had the pleasure of hosting Paul Kennedy, the long-time host of CBC Radio’s Ideas. Paul had come to Montreal to do a story on our research with Black Montrealers. Over two days we listened to archived interviews and walked the streets of Little Burgundy talking about the varied ways that employment mobility made and remade this inner-city neighbourhood over the past 150 years.

One of the interviews that we listed to was with Carl Simmons, a sleeping car porter on the Canadian Pacific Railway, who spoke to the historic importance of railway employment for Montreal’s black community. Until the 1950s, most black men in the city worked for the railway companies as sleeping car porters, dining car employees and red caps. Historian Sarah-Jane Mathieu, in her book North of the Colour Line, argued that the Pullman Palace Car Company “permanently fixed the image of black men to the railroads with the introduction of its opulent sleeping cars in 1865.” This racial practice was exported into Canada when Pullman introduced its palace cars here in the 1870s. The Canadian Pacific Railway and the Grand Trunk (later part of the Canadian National Railways) followed suit.

Pervasive racism in the first half of the twentieth century meant that there were few other employment opportunities for black Montrealers. Our interviews had much to say about this history of racial discrimination. Before Babsey Simmons’ father came to Montreal from the Caribbean, and became a porter, he was a tailor: but “in those days, there were no jobs for Colored men whatsoever, the only job for them was on the train, as a porter, which was a very demeaning job at that point in time. They were underpaid but they did their job with dignity.” Florence Phillips, whose husband was also a porter, agreed: “If they didn’t work on the train, then they worked what? Whatever they could get. It was very, very difficult to get a job here being black.” Few factory or service sector jobs were available to black workers. For their part, black women worked mainly as domestics in the homes of the wealthy. This only began to change in World War II, as a labour shortage led factory owners to hire women and racial minorities. But even then, black workers got the least desirable jobs with the lowest pay.

Black workers might have had the worst paid jobs on the railway, but they enjoyed high status within their community. There are many reasons for this. Black porters were often highly educated, as the CPR in particular recruited its porters from the black colleges of the Southern US. They were also well-travelled. Mobility had its advantages, contributing to the rising political awareness of shared socio-economic and political problems facing blacks across North America. Historian Sarah-Jane Mathieu goes so far as to say that porters were at the political vanguard and helped produce a “powerful diasporic consciousness” in North America. There is certainly ample evidence of this leadership in Little Burgundy.

Montreal’s English-speaking black community took root in Little Burgundy due to its proximity to the Windsor and (the old) Bonaventure train stations. Sleeping car porters, and their wives, helped found virtually every major community institution in existence before the 1960s. The Colored Women’s Club, for example, was formed in 1902 by fifteen wives of sleeping car porters. The local branch of the Garveyite Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), formed in 1919, was likewise formed by porters and was first located in a building, where the CRP housed its non-resident sleeping car porters. The best-known member of this branch was Louise Langdon, mother of US black power leader Malcolm X. For its part, the Union United Church, established in 1907, also had a strong connection to porters. In his published history of the church, David Este wrote that a “small group of American-born railroad porters felt the Bethel AME Church, was not meeting the requirements of all Blacks in the community. Motivated by the need for unity to avoid the discriminatory practices of the White churches and the desire to control their own institutions, the porters, after considerable discussion and debate” formed a new church. The Reverend Charles Este, who came to Montreal in 1923 from Antigua, worked for a time as a porter, and would later serve as a chaplain for one of the railway unions. Even the father of jazz legend, Oscar Peterson, was a railway porter. It is no exaggeration to say that most early black professionals in the city – social workers, lawyers, engineers, university teachers, and medical doctors – were able to go to university because of the paychecks of their railway working fathers and a commitment to education that ran deep within these families.

Black trade unionists were community-builders and early civil rights champions, and their employment mobility had a profound impact on family and community structures. Railway porters also contributed to upward mobility as a community, as they formed their own unions to represent their interests after white unions refused them membership. The history of black trade unionism and collective struggle is a big part of the story of Little Burgundy, but one that has been largely hidden locally.

That part of Montreal between Saint-Henri and Griffintown, north of the Lachine Canal, in the city’s Southwest Borough, was once known by many names: Saint-Antoine district, Ste-Cunégonde, Faubourg St. Joseph, the West End, even as part of Saint Henri. “Little Burgundy” was invented in the 1960s by city officials to describe their urban renewal plans for the area, and the name stuck. If employment mobility was foundational in the making of Montreal’s black community, then it proved just as central to its re-making during the 1960s and 1970s.

The shift from trains to cars and trucks had a three-fold impact on Little Burgundy. First, employment levels collapsed with the decline of passenger train travel leaving many black men unemployed. Then, the state built a highway through the neighbourhood to facilitate the mobility of mainly white suburban workers and consumers making their way to the central city. Much of the black community was in the northern half of the neighbourhood, concentrated along Saint-Antoine. This was precisely the area targeted by the city for the highway. It was no coincidence. The radical restructuring of North American cities disproportionately affected racialized minorities and poor whites. Next, the rest of the deteriorating neighbourhood was urban renewed on a massive scale. These developments were integrally connected. Just as urban decline has deep historical roots and was “ripe with injustices,” so, too, urban renewal. As Ted Rutland argues in his important new study on urban planning in Halifax, Nova Scotia, “[d]isplacing blackness, physically and symbolically, is the unending work of modern planning.” Harsh words, clearly, but ones with the force of history behind them.

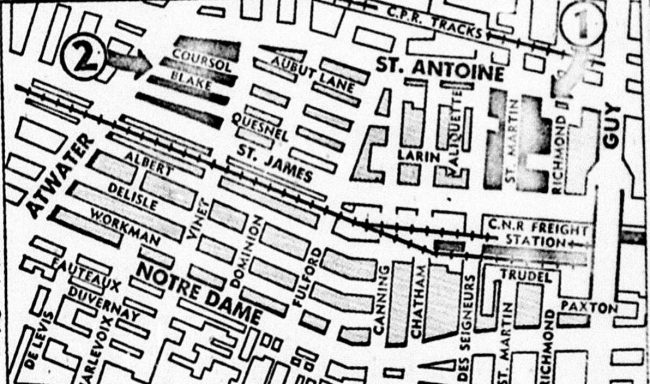

Illustration 6: The early phases of urban development began with the Ilots Saint-Martin (#1 on the map) and followed with Quesnel-Coursol (#2). Montreal Star (31 October 1968).

Many within the community believe the city’s urban renewal project was a disaster. Richard Lord, interviewed by historian Dorothy Williams in the early 1980s, recalled that the demolitions had displaced “people that served their country well, who had deep roots in the area, broke up the community.” Gordon Butt, a community organizer, went further suggesting that “Saint Antoine was one of the richest looking community streets you ever want to see…. The old stone homes that were there were something. You have to see it to understand, the kind of destruction that took place in this community. And where did all those people go?” Adding, “they took away the gut of the community. Everything was stripped.”

There is of course much more to this story, and the connections to employment mobility are sometimes unexpected. But there is considerable value in looking for connections where you least expect them.

For more on this story, check out CBC’s Ideas.

Leave a Reply