Field site: The the tourism corridor of the Canadian Rockies through Jasper National Park, Lake Louise, Banff National Park and Yoho National Park, AB, and Golden and Revelstoke, BC.

From international co-investigator Anna Karlsdóttir, University of Iceland.

The parking lot at the Athabasca Glacier is located where the glacier lay before. A popular tourist spot dominated by recreational vehicles and rental cars. Photo Anna Karlsdottir.

My research in Iceland focuses on employment-related geographical mobility in Iceland’s most visited tourism corridor – called the Golden Circle – encompassing the national park of Þingvellir, Golden waterfalls/Gullfoss and the Geysir area in Haukadalur (the hot spring area Yellowstone National Park hot spring owes its name to). Tourism in Iceland has exploded during the last decade and the number of visitors now exceeds the number of inhabitants three-fold, putting heavy pressure on the carrying capacity of the pristine natural environment which attracts people to the area. Increases in tourism have also led to serious concerns about labour market development and hiring practices in tourism. The labour involved in tourism has shifted during the rapid increase in visitors to Iceland and more and more jobs are done by migrant labour. One characteristic of tourism jobs is the seasonality of tourist activities, making the industry prone to precarious practices. Migrant youth labour is a dominant part of the workforce involved in servicing tourists in Iceland’s Golden Circle.

During the On the Move Partnership, I will be working together with Canadian co-investigator Dr. Angèle Smith, University of Northern BC, whose research encompasses the field site detailed above, which I visited this past summer. We intend to compare similarities and contrasts between Canada and Iceland in terms of employment-related geographical mobility and youth labour in tourism.

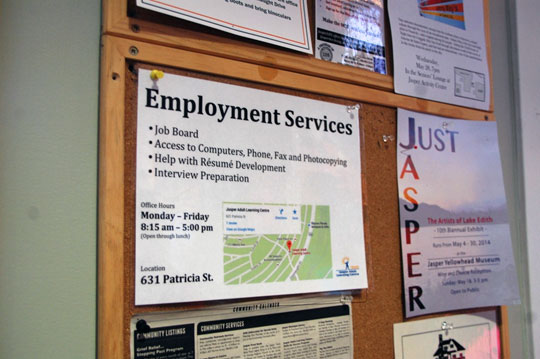

Information board for community and employment services at the Jasper Tourist Information Centre. Photo Anna Karlsdottir.

There are many similarities between this part of the Canadian Rockies and Iceland’s Golden Circle, including physical characteristics which serve as natural tourism draws (glaciers, hot springs. etc.). I was excited to visit the Canadian Rockies to explore its majestic nature and to observe youth labour mobility and tourism in the area.

In addition to email correspondence related to our fields of study, Angèle and I initiated our collaboration by meeting in Prince George in late May. We compared preliminary findings from our research work and Angèle helped me make plans for participatory observation work in the field. We found that a similar dynamic has evolved in tourism labour practices in our research sites in Iceland and Canada. Because tourism workers are involved in face-to-face interactions with travellers, their cultural knowledge, interpersonal and language skills are crucial assets to the tourism industry, but in some tourism sectors, especially those which include traditions of voluntary labor, hiring practices seem to lead to an emerging perception of tourist service jobs as lifestyle tourism rather than real job offerings. This changes the attitude of running a tourism business in many ways.

I would define lifestyle tourism as a precarious job, which is per se seasonal and therefore delimited temporarily. Young aspirant people, many of them still completing their education, occupy jobs using gap years or holidays to earn pocket money in combination with an adventurous experience. Many questions emerge related to this development. For example, how does a reliance on young adventurers/workers affect knowledge content and quality? The cumulative knowledge involved in servicing tourists risks not being stored as it withers away with every worker who finishes their seasonal job and leaves. How does it affect the attractiveness of jobs in tourism in general? Is a low pay, low skill route to job development in tourism inevitable?

A collage of “Help Wanted” signs around Banff. Photos: Anna Karlsdottier.

Job opportunities were obviously numerous at the time I was travelling through. In particular stores in Banff seemed to lack workers. Some people I spoke with explained that the salary for workers in both retail and restaurants was low, while living costs in Banff were high. And unless accommodation is included in your job contract, which is sometimes the case for hotel and motel staff, it is difficult to find a place to rent. We certainly saw prices rise once we arrived within the national park borders.

I observed a stark contrast between the dominant age of tourists and tourism personnel in the field site area. While the majority of tourists were 50 plus, often travelling as couples or in planned tours, tourism industry workers were predominantly young people. When I had the opportunity to ask, I found that many of the young workers came from Ontario, some from smaller or mid-size urban areas where holiday job opportunities were limited. I also met young people off shift from motels and hotels in Banff who came from France, Portugal, Spain and other European countries with high youth unemployment rates. Finding work seemed to be the determinant for the flow to these tourist areas. Working a service job in the Canadian Rockies may be seen as a fun adventure. Some of the personnel I spoke with had just finished school and came to work during their holidays. Given the temporary nature of their employment, their knowledge of the businesses they worked in was sometimes limited. That said, I also met young people who seemed to have been so drawn to the fun of working in this region that they stayed for a couple of years, however, none considered themselves permanent workers.

These brief field notes provide just a glimpse of what I observed with respect to employment-related geographical mobility and youth labour during this initial field site visit. Our hope is that Angèle will be able to make a similar field visit to Iceland next year. I have high hopes and expectations for the On the Move Partnership and consider this project a very interesting opportunity for international comparative research.

Anna drawing her national flag on a blackboard set out on the main street in Banff, which asks which country are you from? Photo: Guðmundur.

Top ^